Australian Water Rights: An Overview of Recent Developments

Author: Adelaide Pope | Finance Director 2021

What are water markets?

Like any other market, water markets connect buyers and sellers, thus allocating “water” through a simple supply-demand mechanism. The Australian water market is often viewed as the world’s most sophisticated water market, and this is of course partly due to how scarce this precious resource is in our dry lands. Embracing this system has been a “drought-proofing” strategy of the Australian government in recent times and has in large part replaced the subsidisation of water and the building of dams.

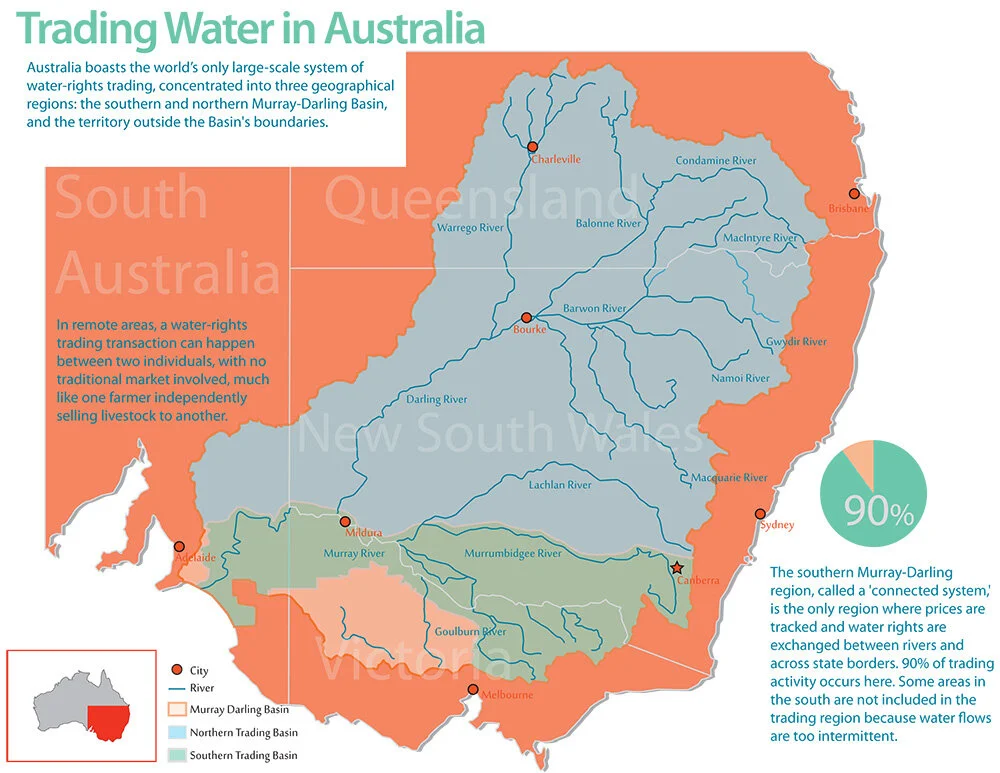

Map of Australia’s Three Water Markets

Source:https://www.circleofblue.org/2013/world/australias-water-markets-succeeding-yet-severe-challenges-loom/attachment/murray-darling-basin-map/

As summarised by the Bureau of Meteorology, water trades in Australia are transactions to buy, sell or lease a water right, in whole or in part. This can be in the form of entitlement trades including the permanent trade and leasing of water entitlements (a right to exclusive access to a share of water), or seasonal water allocation trades (trading of a specific volume of water allocated to water entitlements over a given water year). As alluded to previously, prices of these trades are determined by “the market”—where the buyers’ willingness to pay meets the seller’s willingness to sell. In a closed stochastic system, however, when water cannot be “produced” or even stably forecasted for, prices ultimately reflect intended purposes of use, changing weather patterns, available allocations, storage volumes, jurisdictional legislative arrangements, and commodity market conditions.

Theory, reality and the problem

This is logical. In theory, markets are a fundamental way to create Pareto Efficient outcomes—where the socially optimal allocation of water is such that no party can be made better off without making another worse off. Allocation amounts would be based on users' individual valuations of the water, and trades would be supplemented by transfer payments where needed. Due to this, allocation outcomes will supposedly be more efficient as they would reflect high-value usage of water, and also create more awareness about scarcity, thus encouraging conservation.

In reality, however, the commodification of water and the impact these “efficient” allocations have on people’s livelihoods are much harder to realise. One trend of late is the increased number of participants in the water market who are not buying water rights for use but for investment. In the drought of 2019 when the water price skyrocketed, two of Australia’s biggest non-state and non-agricultural water-owning companies Duxton Water and Blue Sky Water Fund recorded 40% and 34.4% annual returns respectively. These speculators are artificially driving up the price of water in Australia and harming the livelihoods of farmers and their drought-stricken communities.

“My biggest beef by miles is that non-irrigators can buy water and just hoard it, collect it and short the market of it”

After the release of official figures that 14% of water trades in Australia were in fact made by non-landowners, Minister for Agriculture David Littleproud called for the ACCC to review the “the purity of the market”—this became the watershed Murray Darling Basin inquiry.

In this report, the ACCC identified a clear set of problems with the current Murray-Darling Basin market, which is Australia’s biggest and most active water market:

there is a lack of quality, timely and accessible information for water market participants

there are scant rules governing the conduct of market participants, and no particular body to oversee trading activities, undermining confidence in fair and efficient markets.

existence of unfair trading behaviours that can undermine the integrity of markets, such as market manipulation, are not prohibited, insider trading prohibitions are insufficient, and information gaps make these types of detrimental conduct difficult to detect

differences in trade processes and water registries between the Basin States prevent participants from gaining a full, timely and accurate picture of water trade, including price, supply and demand

changing conditions, such as reduced inflows, shifts in water use, declining channel capacity and increasingly binding trade restrictions, are challenging key assumptions that underpin trade arrangements and the design of tradable water rights.

A summary of these findings would highlight the complex and fragmented nature of governance, a lack of regulation, and the lack of information sharing for the use of business decision-making. This environment does not create the necessary preconditions for a fair and efficient market for water trading, thus undermining trust in the effectiveness in these market models and relevant institutions.

“A mismatch between market and physical system. A gaggle of regulators with fragmented and overlapping roles. Untimely, inaccurate and inadequate information. Improper reporting. Conflicts of interest. Professional traders taking advantage.”

Reforming the system

In response to these damning concerns, many market participants have called for the return of a system where water ownership is tied to land ownership, with minimal trade between water users when necessary. In spite of their findings, “the ACCC does not support this position”, but instead recommends a package of reforms that would improve the current market system and allow the wider Australian economy to benefit from its success.

The Murray Darling Basin

Source: https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2020-12-15/murray-darling-basin-plan-evaluation-report-2020-released/12982530

These major reforms would include the establishment of a new “Water Markets Agency” which would have the authority to oversee and regulate the market, including its traders, brokers and other intermediary participants; a mandatory code of conduct imposed on all participants (currently only a voluntary code exists) to level the playing field and regain trust; quality data monitoring, modelling, and sharing across different geographic areas to assist with transparent and accurate information banks; and the reassessment of contextual assumptions so that water markets can operate more efficiently in close connection with the river system’s physical characteristics into the future.

Broadly, by implementing stronger regulatory frameworks and streamlining existing processes, the Australian water market can become a more equitable and efficient method of resource allocation and, subsequently, economic performance. With this increased transparency, non-professional traders and non-large agribusinesses will be better equipped to participate in the market and thus contribute to its coherent function.

Like all recommendations, this is much easier said than done. As the Constitutional responsibility for water management rests with state governments, implementing 90% of these recommendations would require some form of state-to-federal coordination. This bureaucracy and politicisation may even prove to be the most significant barrier.

This stark ACCC report made national headlines and also became the focus for the 2021 Australian Productivity Commission’s three-yearly inquiry into the progress of Australia’s water resources sector (as a part of the Water Act 2007).

The general consensus from the findings of the National Water Reform investigation into the National Water Initiative (NWI) was decisive: “that this 17-year-old paper is not fit for climate change, a growing population, and our changing perceptions of how we value water.”

This inquiry recommended:

making water infrastructure projects a critical part of the National Water Initiative

explicitly recognising how climate change threatens water-sharing agreements between states, users, towns, agriculture and the environment

more meaningful recognition of indigenous rights to water

delivering adequate drinking water quality to all Australians, including those in regional and remote communities, especially during drought

all states committing to drought management plans

“The original NWI focused on making the best use of our water resources; it did not envisage market behaviours such as speculative and tactical trading in water with a view to making profits in the water market itself, rather than profiting from farming.”

What must be done going forward

With the threat of climate change and the likelihood of increased and prolonged droughts, Australia must act now. By 2050 an additional 11 million additional people are expected to be living in capital cities—which means 11 million additional mouths to be fed, showers to be had and 11 million additional toilets to be flushed. If the market for water is left as it currently is, prices will rise so astronomically that the livelihoods of both domestic and industrial consumers will be greatly impacted.

The impending threat of climate change means we need to act now.

Source: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/climate-change-hits-harder-world-must-increase-efforts-adapt

While water markets are far from perfect, new research from the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) has found they are vital in helping the region cope with drought and climate change, producing benefits in the order of A$117 million per year. Due to this potential, and the fact that there is no feasible way to phase out such a large market system, action must be taken to reform and revitalise the current model.

Although the recommended reforms are critical to the long term sustainable performance of the market, a fundamental shift into how we as individuals, and we as a society, view water is also essential. We must remember that water is not inherently a financial asset—but rather a source of life for people and the planet. Being conscious of our consumption, and extending a safe and reliable supply of water to our thousands of rural neighbours who currently lack such things, are the first steps in realising this.

Furthermore, “In order for water markets to realise success”, World Bank 1997 Water Report wrote, “multiple factions within society must be able to view water markets as serving social values and objectives”. A glaring injustice in the water market today is with Indigenous water rights: about 15% of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population live in the Murray-Darling Basin—yet they manage less than 1% of its land base. This share has been declining since 2004 and is unlikely to cease on its own accord.

“If we were to be given an economic water allocation, we could use it in this current climate, to look at Indigenous food security and partnerships in the rural sector, so Aboriginal landholders can look at growing specific Indigenous food products, or cropping, organising and creating employment for these rural communities that are struggling”

In 2007, then Prime Minister John Howard said, “a radical and permanent change [was] needed to Australia’s approach to water management”.

Fourteen years later, we are still waiting for that change.